“I started in renewables 25 years ago, when we were being told that photovoltaics was a pipe dream, similar to what the conversation is today about fusion,” said Jane Hotchkiss, president of Energy Common Good, a Concord-based advocacy group for fusion energy. “It’s not just about technological viability; there are very real ‘soft’ hurdles to overcome getting a new technology to the grid.”

By David Abel, Globe Staff

December 22, 2021

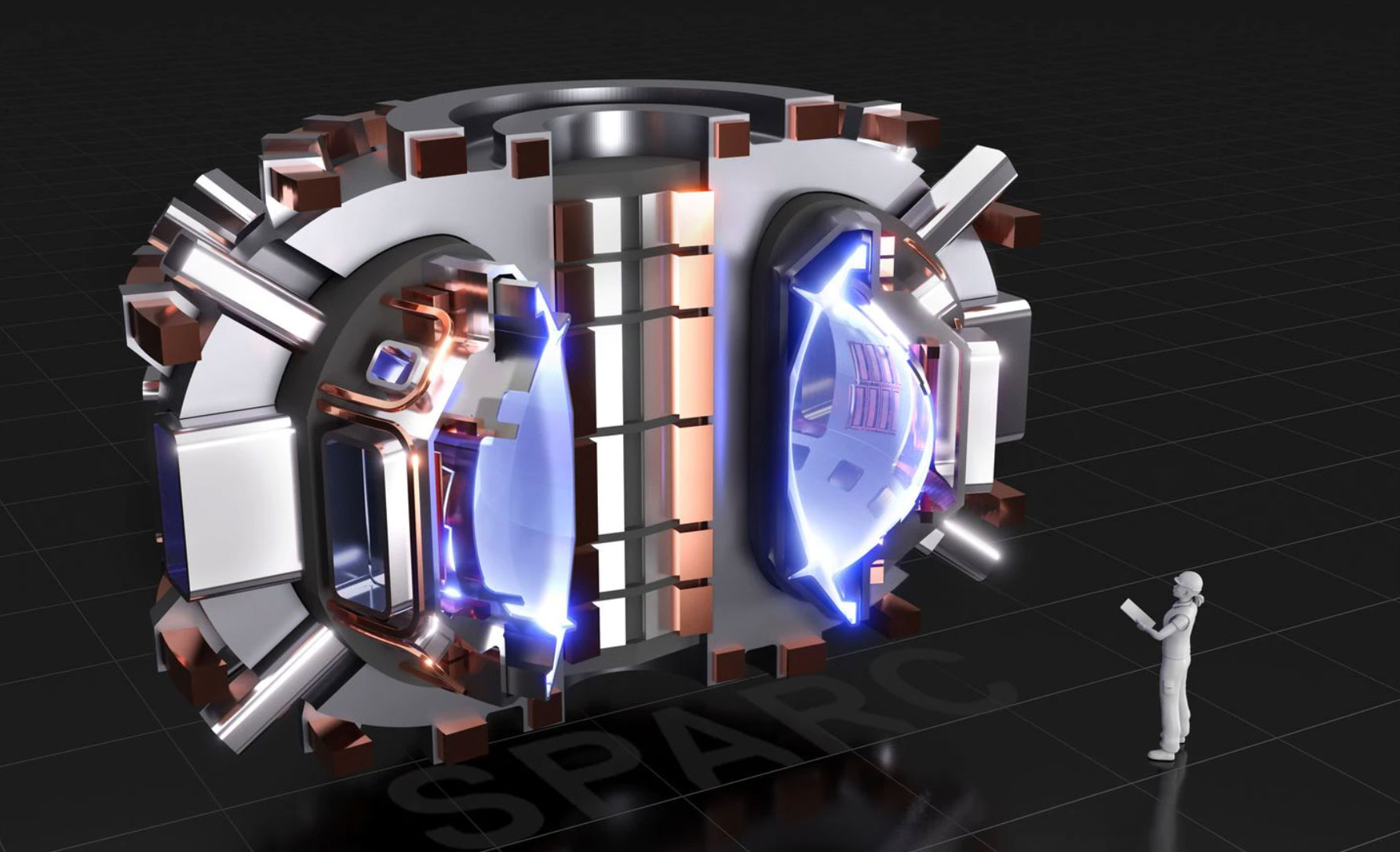

DEVENS — It’s been compared to everything from a holy grail to fool’s gold: the ultimate solution to clean, readily available energy or an expensive delusion diverting scarce money and brainpower from the urgent needs of rapidly addressing climate change.

For decades, scientists have been trying to harness the energy that powers stars, a complex, atomic-level process known as nuclear fusion, which requires heating a plasma fuel to more than 100 million degrees Celsius and finding a way to contain and sustain it. In theory, fusion could yield inexpensive and unlimited zero-emissions electricity, without producing any significant radioactive waste, as fission does in traditional nuclear power plants.